“ここにあるもの”と共に歩む

形になるもの、移ろいゆくもの

2021年のインタビューの後、コロナ禍や気候変動を通して自分たちと周りの社会が変わってきたこと、変えていきたいことを

工房長の軍司昇と統括マネージャーの軍司知恵子がインタビュー形式で語りました。

※企業・学校名については、敬称を省略しています。ご了承ください。(聴き手・フリーライター 細川美香、2025年8月)

インタビュー記事に対し、メディアや企業から反響

―前回(2021年3月収録)のインタビュー掲載後、なにか変化はありましたか?

知恵子 そうですね、わたしたちの考えを知った上でたくさんのお客様が流氷硝子館に来てくれるようになり、「応援しているよ」というありがたい言葉を届けてくれることがとってもうれしいです。

2021年6月にインタビューを公開したことで、すごく話がスムーズになりました。それまでの問い合わせの多くが「工房長 軍司昇とは」、「なぜ網走でガラス?」「流氷硝子館ってなに?」…。その返答に多くの時間を割いて説明をしてきました。

取材などを受ける際に「まずこの記事を読んでください」と伝えることで、内容を理解した上で来てくださる方が増えました。そのおかげで、興味を持ってくれた方とは深い話ができるようになります。

全国規模のメディアで言うと、例えば、2022年1月のEテレ「すイエんサー」への出演、協力。2023年2月の朝日新聞「ひと」コーナーへの掲載。同年7月は森永製菓のモリナガ・サステナブルでキョロちゃんにインタビューをしてもらい、サステナブルな取り組みをしている人を紹介するページで、わたしたちの活動を紹介してくださいました。最近では、NHKワールドの「ゼロ・ウェイスト・ライフ」という番組で海外向けに取り上げていただいています。

昇 企業からの案件としては、ピジョン株式会社から「回収した哺乳瓶(耐熱ガラス)をなにか別のものに生まれ変わらせることはできないか?」という相談がありました。

ただ、哺乳瓶の耐熱ガラスって、わたしたちが普段扱っている“吹きガラス”とは溶解温度が違って、わたしたちの持ち得る機材では溶かすことができません。そこで、酸素バーナーを使って一点集中で形を活かして加工する器や小さなアクセサリーの試作をしたという経緯があります。

知恵子 試行錯誤のやり取りを重ね、最終的には販売ではなく、哺乳瓶の形を活かした耐熱コップにリサイクルし使ってみるという実証実験を行うことになりました。

流氷硝子館に併設しているシーニック・カフェ 帽子岩で約2カ月間ホットドリンクメニュー提供用の器として使用し、お客様にアンケートを実施して反応を集めたんです。その結果をフィードバックして、一旦プロジェクトは区切りとなりました。

昇 教育分野からの反応もあり、例えば美術大学の教授から「素材論の講義で話してもらえませんか?」と依頼をいただいたこともあります。オンラインの講義で、うちの取り組みについて1時間ほどお話させてもらいました。他にも高等学校や教育大学のSTEAM教育(科学 Science、技術 Technology、工学 Engineering、芸術 Art、数学 Mathematicsの5分野を統合的に学び、知識の応用力、発想力、問題解決能力などの「21世紀型スキル」を育む教育方法。)の相談も受けています。

どのケースも、「ホームページ見ました」「インタビュー読みました」というきっかけが多くて、どうしてこの活動を始めたのか、どういう思いでやっているのか、そういう部分をしっかり知った上で連絡してくれるので、話が円滑に進みとても良かったと思います。

企業とのコラボの現状と課題

―ピジョン株式会社とのコラボレーションのように、企業から相談されるケースが増えてきたのですね。

知恵子 はい、そうなんです。わたしたちは小規模な工房なので、その分フレキシブルに対応できることが強みであり、企業からの相談に対応できることはとても光栄なことだと思っています。

ちょうどSDGsが一気に注目され始めたころでしたし、コロナ禍もあって、企業がサステナビリティに注目するようになった。流氷硝子館はオープン時から取り組んでいたからこそ、「ちょっと話を聞いてみよう」「相談してみよう」と思ってもらえたのかもしれません。

昇 株式会社浜田(関西の廃棄物処理業者)から、「太陽光パネルのリサイクルガラスを使って工芸品をつくることができないか?」という相談がありました。そのときはまだ実験段階で、パネルの分別方法が確立されていませんでした。そんな中でわたしたちはガラスを溶かし、そのガラスを使って製作し感じたことや事実をフィードバックし、やりとりを重ね関わらせてもらったことには、やりがいを強く感じました。

その後、太陽光パネルのリサイクルに関する法律の強化に向けて動き出していることや、企業の努力で分別できる技術が進み、再資源化の道筋が見えてきたことが書かれた新聞記事を目にしました。わたしたちが関わらせてもらったことが、少しでも役立てたのかなと思ってうれしかったです。

知恵子 他にも、相談は多方面にわたります。その中で多いのは、「店舗で使えなくなったガラスの器を溶かして新しい製品にしてもらえないか」という内容です。15年前なら、アップサイクルとかリサイクルの取り組みも当然やるべきことであった。でも、今はもう世の中にリサイクル品があふれている状態にもかかわらず、“使った後”のことまで考えられていないケースが多いんです。最初から、リサイクルできる素材を選んで製品を作るのが一番の解決策なのですが…。使った後のことまで考えて購入する商品を選んでほしいと思っています。わたしたちは、事後処理をしたいわけではありません。

昇 そもそもガラスって、素材も違えば、メーカーによって特性も違います。先ほどの耐熱ガラスの話もそうですが、同じ組成のガラスじゃないと混ぜて使うことが難しいです。そのため、意外とリサイクルは進んでいないんですよ。こちらでは、どう加工できるか実験するところから始まる。だから、本当はまず作ったメーカーさんに相談するほうが早いんですよね。

実際は、メーカーが本気で動かない限り、わたしたちのような小さな工房だけでどうこうできる問題ではない部分もあります。板ガラスメーカーが太陽光パネルのガラスを回収して新たに使うという動きを始めたという新聞記事を見つけて、すごくうれしかったですね。製造規模が大きな企業ほどやり方を変えることが難しいことは想像ができます。

知恵子 だからこそ、わたしたちのようなところで試作しないといけないのかもしれないし、「わたしたちでできる範囲でやってみようか」と思えるようにもなってきた。メーカーが本気で廃棄した後のことを考えて製造しなければと思ってくれれば、わたしたちの役割はもう必要なくなるのかもしれませんね。

「オリジナル商品を作ってほしい」という相談も多いんですよ。でもわたしたちにとっては、実は結構リスクがあるんです。例えば、製品がアウトレットになっても、わたしたちの方では売ってはいけないという場合があって。そうなると結局、廃棄することになります。環境活動に注力しているあるアパレル企業は、衣類の寿命を延ばし環境負荷を最小限に抑えるためにオリジナルのロゴ入れサービスを2021年に終了しています。わたしたちも、わたしたちなりのやり方で行動をはじめることにしました。

昇 弟子屈町とコラボレーションして、川湯温泉の湯の花で着色した「川湯温泉ユノハナガラス」では、あえてデザインを変えて、それぞれの土地で違う商品として出しています。そうすることで、網走で買った方が「弟子屈町でも見てみよう」となったり、逆もあったりする。それって、良い循環ですよね。だから、今は「独占を前提としたオリジナル製品」はお断りして、むしろ「お互いにとって良い形」を一緒に考えていく方向でやっています。

夏に溶解炉を止める決断、吹きガラス体験の休止

―企業からの相談が増えた流れで、2023年10月から吹きガラス体験を休止したとか。

知恵子 企業からのご相談の対応に集中するため、吹きガラスの体験を一旦休止する決断をしたんです。限られた日数と人員の中で、製品づくりと社会的な取り組みをどう両立させるか、考えながら動いています。

企業から相談があった場合、試作してフィードバックをもらって…と1~2年かけて進みます。葛藤もありましたが、企業の課題解決への協力を優先すべきだと判断しました。旅行の思い出として吹きガラス体験を楽しみにしていた方には申し訳ないですけれど、「今だけはお休みさせてください」「熱を使わない体験はやっていますよ」「ガラス以外のアクティビティはいかがですか」とお伝えしています。

―夏に溶解炉を止めることも、大きな決断でしたね。

昇 長年ガラス業界にいる私は、とても悩み決断までに時間がかかりました。ガラスって「涼しげ」なイメージがあるから、夏に買いたくなるし、体験したくなる。でも実際は、夏は熱を暖房として利用することもできずに一番無駄にしていて、工房内も40度を超えることもあります。うちは日本で一番涼しい場所にあるガラス工房だと思うんですけれど、それでも夏は暑くて。暑さで意識もうろうとしながら作るって、ちょっと違うんじゃないかなって。そこで2021年に、7月から9月まで溶解炉を止めることにしました。

ここで言っておかなければいけないのは、ガラス溶解炉を止めるからといってお休みでなにもしていないわけではありませんよ。熱を使わない加工の作業や、道具の製作や機材のメンテナンスなどなどこの時期もやることはいっぱいです。

知恵子 流氷硝子館は、主に電気を使って溶解炉を動かしているので、夏場の電力がひっ迫する時期に熱を出してガラスを溶かすという作業自体を見直す必要があると思っていました。年間の製造スケジュールを工夫して、冬場に暖房を兼ねて製造すればいい。止めてみたら、スタッフは「暑くなくて最高」、ご来館するお客様は「ガラス工房なのに暑くない」「海風が通って気持ちいい」。

と喜んでくれました。一方で「どうして止めているの?」と不思議そうに言われるお客様もいますが、説明するうち、少しずつ理解されるようになってきました。

昇 取引先はコンセプトを理解してくれているので、早めに発注してくれたり、2カ月後を見越して動いてくれたりと、スムーズにやりとりができるようにご尽力してくれています。ただ、ガラス業界の中では「暑い中でもガラスを作るのが当たり前」であり、「溶解炉を止めて休む」という発想自体がないのかもしれません。

知恵子 「常識を疑う」って、大事だと思いますね。先日、網走市内の公共施設に行ったら、中が冷房でキンキンに冷えていて…。外は風が気持ち良いので、窓を開けて風を入れれば涼しいはずなのに、冷え過ぎた室内から外に出ると、30度に満たない外気温でもものすごく暑く感じました。

「とりあえず冷房」みたいな思考停止の一択になっているのではないかとすごく怖いです。この地域でその一択はまだ違います。それでまた室外機で排熱して、町全体が暑くなって、さらに冷やす…という悪循環。服装もそう。季節や気温に応じて、その人の感じる温度で対応することが許される社会になってほしいと思います。暑いときは長袖シャツにネクタイじゃなくて、ポロシャツに半ズボンでいいのにと思いますよ。

昇 ちょうどその前後に始めた「コネクトリップ」のガイド事業も需要が伸びて、全体的に良い流れになってきました。夏は製造をお休みしてカヤックガイドに行くのがうちの“夏の新しいかたち”になっています。吹きガラス体験をお休みして網走に来た人が体験するアクティビティがひとつ減っても、代わりにガイドに出る時間が増えて、また別の体験を提供できる。そう考えたら、案外それでいいんじゃないかと思えるようになったんです。

―その「コネクトリップ」は、どのような事業ですか?

昇 きっかけは、2018年に「オホーツク農山漁村活用体験型ツーリズム推進協議会」を網走の仲間と立ち上げたこと。オホーツクには、自分たちの暮らしのすぐ隣に自然と一次産業がある。その魅力を伝えられるガイドを育てる講座をやろう、という話になったのです。

ところが、2020年にコロナ禍で観光が全然ダメになって…。実はわたし、ガラスの修行をしていた沖縄時代に、サーフィンやカヤックなどのウォータースポーツをやっていました。北海道に戻ってきてからも「いつかまたやりたいな」と思っていたので、この時はチャンス!と思いカヌーガイドの方に指導を受けて、3カ月くらいかけて基本をみっちり学びました。そしてガイドを募ってチームを作り、それが「コネクトリップ」の今の形になりました。

条件は厳しいですけれど、冬もやっています。流氷がある海の上をカヤックで進みながら、「流氷があるから魚が育つ」という話をしたり、「実は自分はガラス職人ですよ」という話をしたりして。

流氷硝子館にもお客様が来てくれることもあり、「自分の取り組みが全部つながっているな」と感じます。

夏にガラスの溶解炉を止めるようになったら、午前はガイド、午後はガラス工房という日もありますし、ガイドのお客様が「ガラスも見てみたい!」と来てくれたり。エネルギーを使わずに楽しめるカヤックと、火を使うガラス制作。そのメリハリがまた良いんです。

道内外のガラス工房へ、エコピリカの広がり

―廃蛍光灯リサイクルガラスカレット「エコピリカ」が他の工房でも使われていると伺いました。

昇 そうなんです。ここ数年で継続して注文してくれる方が増えました。ガラス原料の価格が全国的に上がっていて、「代わりになる素材はないか?」と探していた工房さんたちが見つけてくれたんです。一時期は月に何件も問い合わせがあって、正直ちょっと対応が追いつかないほどでした。

わたしたちは2010年に流氷硝子館をオープンした当初から「他の人にも使ってもらえたらいいな」と思って、販売の準備をしていたんです。でも10年くらいはほとんど引き合いがなくて。

知恵子 送料が高くて、道外の工房さんには採算が合わないケースもありました。でも、北海道の多くのガラス工房は東京から原料を取り寄せているので、逆の立場になっただけとも言えます。輸送コストがかかってもリサイクルガラスを使いたいと言ってくださる方がいるのは、本当にありがたいです。最近は個人の方や学生さんからの「卒業制作で使いたい」「環境に配慮した材料を使いたい」という注文もあって、そういうのはすごくうれしいですね。

―蛍光灯の製造が終了したら、エコピリカはどうなるんでしょうか?

昇 蛍光灯の製造が終了し、リサイクルガラスがいずれなくなることも、始めた時から分かっていました。でも、それも含めて伝えながら、今できることを丁寧にやっていきたいと思っています。

わたしたちは「廃蛍光灯リサイクルガラスカレット」に「エコピリカ」という名前を付けました。その理由は、原料として循環してほしいと思ったからです。流氷硝子館で製作した製品に「エコピリカ」のシールを貼って「エコピリカ」の刻印をしています。使い終わったら回収して再利用するときに判別するためです。絶対に無くならないものなどないので、わたしたちはなるべく自分たちのつくったものを回収しながら、長く使っていきたいなと思っていて。ただ、やっぱり飛行機で移動する方が多いので、壊れたガラスを持ってくるのは、ちょっとハードルが高いですよね。

そこで、「エコピリカ」を使う工房が広がっていくことで、それぞれの工房で作られたエコピリカの製品を他の工房で回収してもらって、それが循環していけば、蛍光灯がなくなっても資源として回っていくじゃないですか。そういう世の中に、少しずつなっていけたらと思っています。「エコ(エコロジー)ピリカ(アイヌ語で正しい、美しい)」という名前にしたのも、そんな思いがあります。

再生された原料から生まれる製品たち

―破材や回収したガラスで、新たな製品も生まれているんですよね。

知恵子 はい。ガラス工房を10年以上やっていると、「いつか使おう」と思って取っておいた着色したガラスの破材がどんどん溜まっていったんです。網走や流氷のイメージに合う青の製品が一番売れるので、これが一番破材も多い。色についても、こちらが「この青はちょっと基準より薄いな」と思っても、「お客様にとってそれって関係あるのかな?」と考え始めたりして。自分たちが「この青がいい」と決めているだけで、ちょっと違う青でもいいのではないかって。

そうなると、「あるのに使わない」という状況にモヤモヤしてきて。バージン材料をわざわざ使って色を合わせるよりも、今ある破材をどう活かすかを考えようと、破材や回収したガラスで作る「リンネ(リンク)」ができたんです。

昇 色は、1番が青、2番が水色、3番がオレンジで、4番が緑。狙って作ったというより、偶然きれいな色ができた、みたいな。どんな色になるか分からないからこそ、毎回ちょっとワクワクするんですよね。

幻の3番というのも実はあるんです。本当はピンクを3番にしようと思っていたのですが、ピンクの破材を溶かしてみたら、透明になっちゃって…。鉄分とか他の成分の影響で、色が飛んでしまったようです。なので、幻の3番は封印されました。今はもう、それも他の色と一緒に混ぜて、普通の製品に使っています。新しい実験をしても、うまくいかないことのほうが多いですけれど、それでもやってみないと分からないですから。

―新たな色や取り組みについて、最近のエピソードがあれば教えてください。

昇 一時休止していた「バッテリーブラウン」の製造を再開したんです。もともと「バッテリーブラウン」は、乾電池のリサイクル原料から作った色で、中に入っている成分の一部がガラス溶解炉の「るつぼ」を侵食してしまうことが分かって、7~8年前に製造を中止したという経緯があります。でも、エコピリカを提供してくれる野村興産株式会社イトムカ鉱業所といろいろ話していく中で、「改良することができるかも」となって。試行錯誤の上で、結果的にるつぼの侵食もなくなりました。

知恵子 お客様や取引先からも「茶色のガラス製品を待っています」という声をずっといただいていて、なんとか復活させられないかと相談を重ねてきました。そうして去年、ようやく復活。安定した色も出せるようになりました。

乾電池や蛍光灯って、誰でも知っているじゃないですか。だから「えっ、あれがこんな綺麗なガラスになるの?」と、反応も大きいんですよね。透明なガラス製品はよくあるけれど、茶色は意外と少ないというのも良い点です。クリアとリンネ、バッテリーブラウンの茶色など流氷硝子独自の色味が増えてきた今、「これが流氷硝子の目指すものづくり」と感じています。

オープン当初から現在も「赤いガラスはないの?」とか「金箔を使った商品は?」「色が少ない」と言われています。でも、わたしたちは地元にある資源を使うことを大事にしているんです。そういった考え方を、ようやく形で示せるようになってきました。

周囲やお客様からの反応と、大切にしていきたいこと

―流氷が減っているという話題も出ていましたが、お客様の反応はいかがですか?

知恵子 流氷観光シーズンの冬にご来館するお客様の中には、「流氷が見られなかった」とがっかりする方がいます。流氷が当たり前に存在していると思う方も多いですが、今はそうではない。環境は変わっている、わたしが網走に来た15年前と比べても変わっている。そういう話をすると、驚く方がとても多いです。

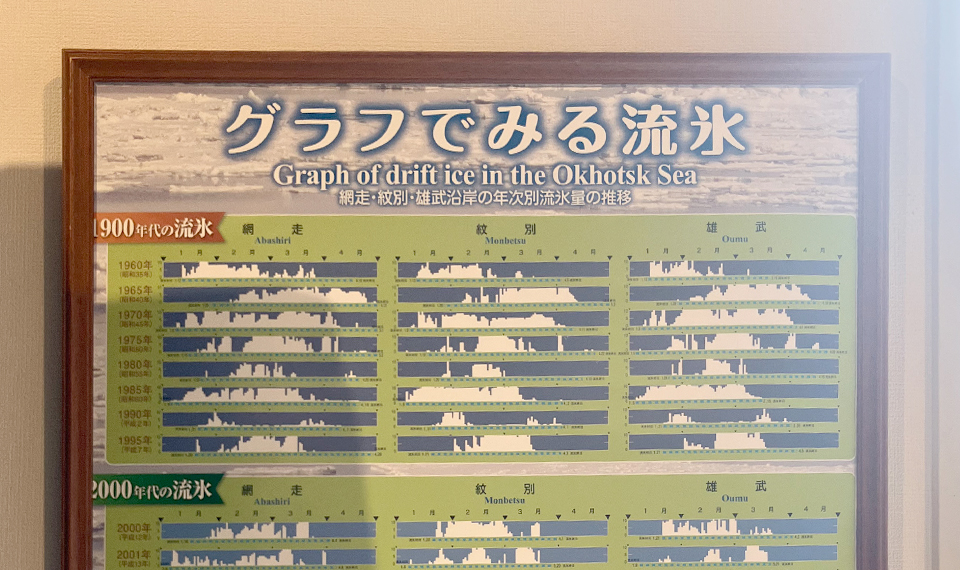

お店の壁に流氷の量の推移を示したグラフを張って、「これ見てくださいね」と声を掛けるのも現状を知ってもらうきっかけの一つです。海外から来られるお客様が流氷が減っていることに危機感を持っていることも多く、国内の方のほうが意外と流氷のことを知らない場合もありますね。「ガラスがきれいだから」とか「旅行のついでに寄ってみた」というお客様にも環境の話を少しでも届けられるなら、すごく意味があるなと思っています。

流氷はこの地域に住むわたしたちにとって、環境の変化を感じ取るバロメーター。きっと他の地域にも似たような現象があると思います。例えば特定の虫が大量発生したり、いつもと違う時期に花が咲いたり。そんなちょっとした変化にアンテナを張ることも大事ですね。

昇 今は、小学校の修学旅行で来てくれる学校が増えています。ガラス作りを体験してもらったあとに、環境やリサイクルについて話しています。地元の中学校から講話の依頼が来ることもありますし、ガイドのような形で地域の紹介をすることも。自分がこの場所でモノづくりをして暮らしているという話を中学生や高校生に伝えることにも、やりがいを感じます。

―これから大切にしていきたいのはどのようなことですか?

知恵子 たとえお店がなくなったり事業承継することになっても、わたしたちの「取り組み」や「考え方」は残っていけばいいなと思っています。別にガラスに特別こだわっているわけでもないので、材料がなくなって、やっていることが受け入れられなくなったら、縮小するなり、やめていくことになると思いますし、次のなにかをしなければいけませんね。

昇 それでも、やっぱり「なにかを作りたい」という気持ちはずっとありますね。ガラスで言えば、夏はやめて冬だけ作るとか、土地や環境に合わせた働き方ができる世界が実現したら、他のものに切り替えてもいいかなと思っているんですけれど…。でも、今のガラス業界がリサイクルを前提とした方向に切り替わるまでは、まだ自分たちがやらなければいけないなと思っています。

夏は暑いから溶解炉を止めることや、涼しい網走で冷房に頼らないこともそうですが、もっと「シンプルに」「わかりやすく」ありたい。「これ、当たり前に見えるけれど、本当にそうなのかな?」というちょっと疑ってみるという感覚を大事にしたくて。「思考停止しないこと」、それはまさに自分たちが日々やろうとしていることです。

カヤックガイドをしていて、海や魚の変化も感じます。最近は網走でも、鮭が獲れなくなり、フグやブリが獲れるようになる「魚種交代」という現象が起きているらしいんです。簡単に言うと、海水温の変化で、今まで南の方にいた魚が北の方に上がってくる。それって単純に「じゃあ別の魚を獲ればいい」って話じゃないんですよね。

例えば、鮭って川を遡上して、最終的には森に栄養を届けているんですよ。もし鮭がいなくなったら、山や森の生態系まで変わってしまう。森への栄養の循環が止まったら、地元の自然が持続できなくなるかもしれない。魚の背景にある根っこの部分が崩れてしまうことが怖いなと感じています。

知恵子 お客様に製品をお渡しする時に使う梱包材も、できれば減らしたい、無くしたいと考えていますが、実際は進んでいません。お客様が持ち帰る状況はさまざまなので、どうしても「絶対に割れないように」配慮すると梱包材が過剰になってしまいます。お客様も、「いらない」とは言いづらいと思います。今後はどのような形をスタンダードにするか。あるいは、お客様が選べるようにするのか、みなさんと一緒に考えていきたいと思っています。

―お客様や社会に向けて伝えていきたいことは?

昇 環境に関して伝えたいと言えば、今は電力について発信したいと考えています。2021年にウェブサイトをリニューアルした際に「電力会社を変える」ことも発信しました。わたしたちは、企業理念に共感した「ハチドリ電力」という電力会社を選びました。

「電力の自由化で電気代が安くなる」というところまでは聞いたことがある人が多いけれど、その仕組みが意外と分かりにくい。電気そのものは同じだけれど、支払ったお金がどんな理念で動いている企業に届くのかが、とても大事なことだと思います。そのお金が支援になって、循環する。だから、意志を持って選ぶということが大事なんです。

知恵子 考えていることやめない、思っていることは発信していくことを続けたいです。なにげないことも環境問題でもなんでもそうですが、「興味あります」という言葉はよく聞くけれど、どう行動すればよいかわからないという人も多い。でも本当にすべてのことが自分のことだと思って、自分につながっていることだと思って、なにかひとつでも行動する人が増えないと意味ないですよ。

昇 エシカル消費やSDGsへの世の中の関心が、流行りで終わってほしくない。継続して取り組まなければいけないことです。自分の理念に従い、ライフワークとしてわたしができることを続けていきたいと思います。

プロフィール

工房長 軍司 昇(gunji noboru)

統括マネージャー 軍司 知恵子(gunji chieko)

Moving forward with “things that exist among us”

Things that take shape, things that transition

Following their 2021 interview, Workshop Director Noboru Gunji and General Manager Chieko Gunji discussed in this interview how the pandemic and climate change have affected both their personal perspectives and the society around them, focusing on the changes they hope to see emerge.

※Please note that business and school names are listed without honorifics.

(Interviewer: Freelance writer Mika Hosokawa, August 2025)

Feedback from media outlets and companies regarding the previous interview

– Since the last interview, published in March 2021, have there been any changes?

Chieko: Well, it’s truly heartwarming that so many customers come to the Ryuhyo Glass Museum after learning about our philosophy and share kind words like, “We’re rooting for you!”

Releasing the interview in June 2021 made communicating with everyone much easier. Before that, many inquiries were along the lines of “Who is Studio Director Noboru Gunji?”, “Why make glass products in Abashiri?”, “What is Ryuhyo Glass Museum?”- I spent an excessive amount of time responding to these inquiries.

Now, I tell new interviewers to first read the article about us so they come in with a better understanding of our story. This allows me to have deeper conversations with those interviewers who show genuine interest.

Nationwide media appearances include, for example, an appearance on and collaboration with NHK Educational TV’s “Suiencer” in January 2022, and a feature in the “People” section of the Asahi Shimbun newspaper in February 2023. In July of the same year, Morinaga Confectionery’s “Morinaga Sustainable” project featured us on a page introducing people engaged in sustainable initiatives, where Kyoro-chan interviewed us. More recently, we were featured internationally on NHK World’s program “Zero Waste Life.”

Noboru: One corporate project involved a request from Pigeon Corporation inquiring if we could transform collected heat-resistant baby bottles into something else?

However, the melting temperature of heat-resistant glass used for baby bottles differs from that of “blown glass” we typically work with and is impossible to melt with our existing equipment. So, we experimented with prototypes and small accessories using an oxygen torch to shape them with precise, concentrated heat while utilizing their form.

Feedback from media outlets and companies regarding the previous interview

Chieko: After repeated trial-and-error exchanges, we ultimately decided to conduct a proof-of-concept experiment. Instead making products for sell, we would try out the heat-resistant cups made by utilizing the original shape of the baby bottles to test their usability.

For a few months, we used the prototypes at the Scenic Cafe Boshi Iwa, located adjacent to the Ryuhyo Glass Museum, to serve hot drinks on the menu. We collected customer feedback through surveys. We provided input on the survey results and concluded the project for the time being.

Noboru: We have also received responses from the education sector. In one instance, a professor from an art college asked me to speak at his materials theory lecture. I ended up giving a roughly one-hour online lecture about our initiatives. We have also consulted with high schools and teacher training colleges on STEAM education. (STEAM is an educational method that integrates the study of five fields – Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics – and fosters “21st century skills” such as the ability to apply knowledge, creativity, and problem-solving.)

In all cases, the initial contact came from people who found our website or read our interview. Because they reached out after thoroughly understanding why we started this shop and our intentions, the conversations progressed smoothly, which turned out to be very positive.

Current status and challenges with corporate collaborations

– So, you have seen an increase in cases where companies approach you for consultation, such as your collaboration with Pigeon Corporation.

Chieko: Yes, that’s right. As a small workshop, our strength lies in our flexibility, and we consider it a great honor to be able to accept such inquiries from companies.

It was around the time SDGs started gaining significant attention. And also with the pandemic, companies began to focus more on sustainability. Perhaps because the Ryuhyo Glass Museum had already been working on this since its opening, people thought to hear what we had to say and to consult us.

Noboru: Hamada Co., Ltd., a Kansai-based waste disposal company, approached us with the inquiry if we could create glassware using recycled glass from solar panels. At that time, it was still in the experimental stage, and methods for separating the panels were still being developed. Despite this, we melted the glass, tried it for production, and provided feedback on our experiences and findings. It was deeply rewarding to have been able to participate in this project.

Later, I came across a newspaper article discussing efforts underway to strengthen laws regarding solar panel recycling, and how advancements in sorting technology, driven by corporate initiatives, are paving the way for resource recovery. It made me happy to think that our involvement might have contributed in some small way.

Chieko: Other inquiries cover a wide range of topics. Among them, a common request is whether we can melt down our own glassware that can no longer be used, and turn it into new products. Fifteen years ago, initiatives like upcycling or recycling were expected as the norm. But today, the market is flooded with recycled goods, and many still fail to consider what happens “afterwards” with their products. The best solution is to choose recyclable materials from the onset when creating products. We hope people will choose products with the product’s post-use fate in mind. We don’t want to be the ones left to clean up afterwards.

Noboru: First and foremost, glass varies in material and properties depending on the manufacturer. As mentioned earlier, with heat-resistant glass, it is difficult to mix and use different types of materials unless they share the same composition. That’s why recycling glass has not been as advanced as you think. Here in our shop, we always start by experimenting with how each type of glass can be processed. So, honestly, it’s faster to consult the original manufacturer first.

In reality, there are aspects that small workshops like ours simply cannot tackle alone unless manufacturers genuinely step up to meet the challenge. I was thrilled to find a newspaper article reporting that flat glass manufacturers have started collecting and reusing glass from solar panels. It’s easy to imagine that the larger the manufacturing scale, the harder it is to change standardized practices.

Chieko: That’s precisely why we might have to continue our work on prototypes here at our workshop. We have started to think in terms of what we can do within the realm of our capabilities. If manufacturers seriously start considering what happens after disposal when they produce goods, then perhaps our role won’t be needed anymore.

We often get requests to create original products. But for us, it actually involves quite a bit of risk. For example, after a product is discontinued, we may be prohibited from selling the items. This leads to usable products being discarded. One apparel company that took environmental initiatives seriously discontinued printing custom logos in 2021 to extend the lifespan of clothing and minimize environmental impact. We, too, have decided to start taking action in our own way.

Noboru: In collaboration with Teshikaga Town, we intentionally varied the design of the “Kawayu Onsen Yunohana Glass” products, colored with mineral deposits from the hot springs of Kawayu, to offer unique items at each location. This encourages customers who shop in Abashiri to think about checking out another version in, for example, Teshikaga Town, and vice versa. This creates a positive cycle, right? So now, we decline requests for “exclusive original products” and instead focus on working together to find “mutually beneficial approaches.”

The decision to shut down the melting furnace in summer, and the overall suspension of glassblowing workshops

– Following an increase in inquiries from companies, you have suspended your glassblowing workshops since October 2023.

Chieko: To focus on responding to corporate inquiries, we’ve decided to temporarily suspend the glassblowing workshops. Within our limited time and personnel, we base our work on balancing product creation and social initiatives.

When we receive inquiries from companies, we start by creating prototypes. Then, we gather feedback over a period of one to two years. Although we ran into conflicts, we decided that prioritizing our cooperation in resolving corporate challenges was the right approach. We sincerely apologize to those who were looking forward to the glassblowing experience as a memorable part of their trip. We tell them that we need to take a break for now as we offer options such as workshops that don’t involve heat or one of our other activities that don’t involve using glass.

– Shutting down the furnace in the summer was also a major decision, right?

Noboru: I agonized over it and took a long time to come to my decision. Glass has this image of “coolness,” so people want to buy it and experience it in the summer. But in reality, summer is when heat is wasted the most―we can’t even use the produced heat for indoor heating―and our studio can exceed 40 degrees Celsius. I believe our shop is the coolest workshop, climate-wise, out of all glass workshops in Japan. Yet it’s still unbearably hot in the summer. Working while dazed from the heat just felt wrong. So, in 2021, I decided to shut down the melting furnace from July to September.

One thing I should mention is that just because we shut down the furnace doesn’t mean we take a break and do nothing. There’s plenty to do during this period, too―processing work that doesn’t require heat, making tools, maintaining equipment, and so on.

Chieko: The Ryuhyo Glass Museum primarily uses electricity to power its melting furnaces. We felt it necessary to rethink the very process of generating heat to melt glass during the summer months when electricity is in short supply. By adjusting our annual production schedule, we could manufacture glass during the winter while also using the heat from the furnace for heating. When we stopped the furnaces, our staff were delighted, saying, “It’s not hot anymore―this is great!” Visitors also expressed joy, remarking, “It’s a glass workshop, yet it’s not hot,” and “The sea breeze feels wonderful.” On the other hand, some visitors did ask, puzzled, “Why did you stop?” But as we explained our reasoning, they gradually came to understand.

Noboru: Our clients understand our concept, so they place orders early and make plans two months in advance, making every effort to ensure smooth communication. However, within the glass industry, it is simply taken for granted that glass production continues even in the heat, and the simple idea of shutting down the furnace to take a break may not even exist.

Chieko: Questioning common sense is important, I think. The other day, I went to a public facility in Abashiri, and inside it was freezing from the air conditioning… Since the breeze outside felt pleasant, opening the windows to let in the wind should have been enough to cool the indoors. Stepping outside from the overly chilled indoors, made the outside temperature, under 30 degrees, feel excessively hot.

I am terrified that we have fallen into this default mindset of automatically turning on the AC just because. That one-size-fits-all solution doesn’t fit here. The outdoor AC units dump heat back into the streets, making the whole town hotter, forcing us to try to cool down even more… It’s a vicious cycle. The same goes for clothing. I wish we lived in a society where people could dress according to the season, the temperature, and how they actually feel. When it’s hot, why can’t we just wear a polo shirt and shorts instead of a long-sleeved shirt and tie?

Noboru: Around the same time, demand for our Connectrip guiding service also started growing, creating a positive overall trend. Taking a break from glass production in the summer to go kayaking has become our “new summer tradition.” Even if people visiting Abashiri find one less activity because we don’t offer our glassblowing workshop, the extra time spent guiding allows us to provide different experiences instead. Thinking about it that way, I’ve come to realize it might actually be just fine as is.

– What is “Connectrip”?

Noboru: It started when I launched the Okhotsk Rural Tourism Promotion Council with friends in Abashiri in 2018. In the Okhotsk region, nature and primary industries coexist right alongside our daily lives. We decided to create a program to train guides who could convey that appeal.

However, tourism completely collapsed during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020… Actually, back when I was training in glassmaking in Okinawa, I used to do water sports like surfing and kayaking. Even after returning to Hokkaido, I kept thinking I would love to do that again someday. So, when this opportunity came up, I thought, “This is it!” I took lessons from a canoe guide and spent about three months thoroughly learning the basics. Then I recruited guides to form a team, and that became the current form of Connectrip.

The conditions are tough, but we operate in winter as well. Paddling across the sea with drift ice, we share stories about how the drift ice helps fish grow, or I get to reveal that I actually am a glass artisan. Sometimes these clients end up visiting the Ryuhyo Glass Museum, which makes me feel that all of my endeavors are somehow connected.

Now that I shut down the furnace in the summer, some days I guide in the morning and work in the glass studio in the afternoon. Sometimes, guests from my tours tell me they would love to see my glasswork and stop by. Kayaking, which requires no energy. And glassmaking, which uses fire; this contrast to me is really nice.

The use of Eco Pirika spreads to glass workshops around Hokkaido and beyond

– I heard that the recycled fluorescent lamp glass cullet, Eco Pirika, is also being used by other workshops.

Noboru: That’s right. Over the past few years, we’ve seen a steady increase in repeat orders of Eco Pirika. With raw material prices rising nationwide, workshops searching for alternatives found us. For a while, we were getting several inquiries a month―honestly, it was almost too much to handle.

We had been preparing to sell Eco Pirika since opening the Ryuhyo Glass Museum in 2010, thinking it would be great if other workshops could also use it. But for about ten years, our wish was never realized.

Chieko: Shipping costs were so high that it wasn’t profitable for workshops outside Hokkaido. But since many glass studios in Hokkaido source their materials from Tokyo, you could say we were just on the opposite side of the equation. We were truly grateful that people still wanted to use recycled glass, even with the added transportation costs. Recently, we have also received orders from individuals and students who wish to use it for their graduation projects or prefer environmentally conscious materials. These encounters make us really happy.

– What will happen to Eco Pirika once fluorescent lamp production comes to an end?

Noboru: We knew from the start that fluorescent lamp production would eventually come to an end and that recycled glass would eventually run out. But even with that in mind, we want to carefully do what we can now while communicating this reality.

We named our recycled fluorescent lamp glass cullet Eco Pirika because we wanted it to circulate as raw material. We affix an Eco Pirika sticker and engrave the Eco Pirika mark on products made at the Ryuhyo Glass Museum. This helps us identify them for collection and reuse after use. Nothing lasts forever, so we want to collect what we make and use it for as long as possible. However, since most people travel by plane, bringing broken glass back to our shop is a bit of a hurdle.

That’s why we envision a world where workshops using Eco Pirika would expand. If products made from Eco Pirika in one workshop can be collected by another workshop, and this cycle continues, then even when fluorescent lights are no longer used, the resources can still circulate. We hope society can gradually move towards this kind of world. Naming it “Eco (from ecology) Pirika (meaning ‘correct’ or ‘beautiful’ in the Ainu language)” also reflects this aspiration.

Products generated from recycled materials

– So, is it correct that new products are also being created from broken and recycled glass?

Chieko: Yes. After running the glass studio for over ten years, the colored glass scraps we had saved, thinking we would use someday, just kept piling up. Blue products matching the image of Abashiri and drift ice sell the best, so we have the most scraps of that color. Regarding color, even if we thought that one of the blues from one of the glass products was a bit lighter than our standard, we began to wonder if a slight difference in color really mattered to our customers. Maybe it was just us being too particular about the “best” blue, when, in fact, a slightly different shade of blue could be just as acceptable.

That left us feeling frustrated about having materials but not using them. Rather than going out of the way to use virgin materials to perfectly match colors, we decided to focus on how to make use of the scrap glass we already had. This is how “Rinne” which is made from scrap glass and recycled glass, was born.

Noboru: For the colors, No. 1 is blue; No. 2 is light blue; No. 3 is orange; and No. 4 is green. It’s less about aiming for specific colors and more about accidentally creating beautiful ones. It’s precisely because I never know what color will turn out that makes me a little excited every time.

There was actually a phantom color No. 3. I originally planned to make pink No. 3; however, when I melted the pink scrap material, it turned transparent… It appears that the color vanished due to a chemical reaction between iron and other components. So, the phantom color No. 3 was sealed away. Now, I mix it with other colors and use it in regular products. When I try new experiments, things often don’t work out as planned. But you never know unless you try.

– Please tell us about any recent developments related to new colors or initiatives.

Noboru: We’ve resumed production of products using the color Battery Brown, which had been temporarily suspended. Originally, Battery Brown was a color made from recycled dry cell batteries. However, about 7 to 8 years ago, we stopped production because we discovered that some components within it were corroding the crucible in the glass melting furnace. However, through discussions with Nomura Kōsan Co., Ltd.’s Itomuka Mining Office, which supplies us with Eco Pirika, we thought that we could work on the problem. After trial and error, we ultimately eliminated the crucible corrosion.

Chieko: We have been receiving requests from customers and business partners who were waiting for brown colored glass products, and we’ve been discussing how we could possibly bring them back. Finally, last year, we managed to revive them. We have also achieved consistent color production.

Everyone knows about dry cell batteries and fluorescent lights, right? So, people react strongly, like, “Wait, what? Those things turn into such beautiful glass!?” While clear glass products are common, brown glass products are surprisingly rare, which is another plus for us. Now that we’ve developed more unique Ryuhyo Glass colors such as Clear, Rinne, and Battery Brown, I feel this truly symbolizes the craftsmanship the Ryuhyo Glass Museum aims for.

Since opening, we’ve consistently heard requests and comments like, “Don’t you have red glass products?” or “What about products using actual gold?” or “There aren’t enough colors.” But we place great importance on utilizing local resources and have finally reached a point where we can tangibly demonstrate our philosophy.

Reactions from the community and visitors, and what we want to cherish

– We have discussed the topic of decreasing drift ice. How do visitors react to the situation?

Chieko: Among the guests who visit during the winter’s drift ice tourism season, some are disappointed because they didn’t get to see the drift ice. Many people assume there will always be drift ice, but that is no more the case. The environment has changed―it’s different even compared to when I came to Abashiri fifteen years ago. When I talk about this, many people are extremely surprised.

Having them take a look at a graph posted on our shop wall showing the trend in drift ice volume is one way to help people understand the current situation. Many international visitors express concern about the decline in the amount of drift ice, while surprisingly, domestic customers often know less about the situation. Even if it’s just a tidbit, I think it’s incredibly meaningful to share environmental realities with customers who simply come in for the beautiful glass products or just happen to stop by while traveling.

For us who live in this region, drift ice is a barometer for sensing environmental changes. I’m sure other areas have similar phenomena occurring around them. For example, a sudden mass emergence of a specific insect, or flowers blooming at an unusual time. Keeping an eye out for such small changes is as important.

Noboru: Nowadays, more elementary schools are bringing their students here on field trips. After they experience glassmaking, we talk about the environment and recycling. We also get requests from local middle schools for lectures, and sometimes we act as guides introducing the area. I find it rewarding to share with middle and high school students how I make a living creating things right here in this place.

– What are the things you want to cherish going forward?

Chieko: Even if the shop closes or the business is passed on, I hope our efforts and philosophy will remain. It’s not like we are particularly fixated on glass making, so if the materials disappear or what we are doing becomes unwanted, we will likely scale back or stop altogether. Then we’ll have to find something new to do.

Noboru: Even so, I still have this constant urge to create something. When it comes to glass, I sometimes think that if we could achieve a world where we could adapt our work to the surrounding land and environment―such as stopping production in the summer and only making glass products in the winter―then maybe we could switch to something else besides glass making… However, until the glass industry shifts toward a model based on recycling, I believe we must continue to take the lead in our actions.

Summer is hot, so we shut down the melting furnace and avoid relying on air conditioning in the relatively cool climate of Abashiri. But more than that, we just wish to be simpler and more straightforward. We want to keep entertaining our senses by questioning the obvious and norms. “Not ceasing to think”―is precisely what we strive to do every day.

As a kayak guide, I notice the changes in the ocean and with the fish. Recently, even in Abashiri, a phenomenon known as “species shift” appears to be occurring, where salmon are no longer being caught, and instead, pufferfish and yellowtail are being caught. Simply put, changes in sea temperature are causing fish that used to be in the south to move northward. It’s not as simple as just saying, “Well, then we’ll just have to catch different fish.”

For example, salmon swim upstream, ultimately delivering nutrients to the forests. If the salmon disappear, the ecosystem of our mountains and forests would change. If the cycle of nutrients to the forests stops, the local natural environment might become unsustainable. I feel a sense of dread that the very foundation underlying the environment of our fish could collapse.

Chieko: If possible, we would like to reduce or even eliminate the packaging materials used when delivering products to customers, but we have made little progress. There are various circumstances in which customers take products home. If we try to ensure that the product “absolutely does not break,” we end up using an excess amount of packaging materials. It seems it is difficult for customers to say they don’t need the extra packaging. We would like to find a solution together on what the standards should be for packaging, or perhaps have an option in which we let the customers decide.

– What do you want to convey to your customers and to society?

Noboru: When it comes to environmental issues, I now wish to focus on spreading information on electricity. When we redesigned our website in 2021, we also announced that we were switching electricity providers. We chose a company called Hachidori Electric because its corporate philosophy resonated with us.

Many people have heard that electricity deregulation lowers bills, but the mechanism behind it is surprisingly hard to grasp. While the electricity itself remains the same, I believe it’s crucial to understand which companies―driven by what principles―receive the money we pay. That money supports the cause and keeps it in circulation. That’s why choosing with intention matters.

Chieko: I want to continue thinking and continue sharing my thoughts. Whether it’s something trivial or related to environmental issues, I often hear people say they are interested; however, many don’t know how to take actual action. But unless more people truly take ownership, realize we are all connected, and take steps toward action, it is meaningless.

Noboru: I hope society’s interest in ethical consumption and SDGs does not just fade away as a passing trend. These are things we must all continue to work on. As my life’s mission, I want to continue doing everything I can, guided by my own principles.